New set of ancient texts (including Daodejing) discovered

NOTE: This post is based on my misreading of an ambiguous New York Times article, as Scott Barnwell notes in the comments. I’m leaving it here because the Tsinghua find remains interesting. It just didn’t include a Daodejing.

For a more accurate and up-to-date discussion of the oldest known DDJ texts, see this newer post.

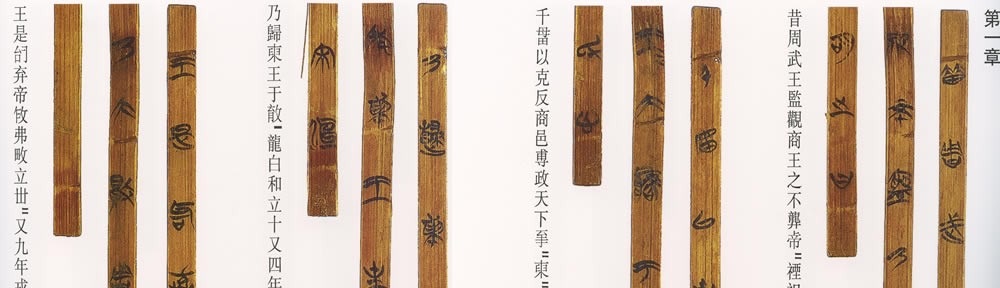

Our understanding of the Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) and other very early Chinese philosophical texts owes a lot to two archaeological finds, the Mawangdui Silk texts and the Guodian bamboo slips, in 1973 and 1993 respectively. Each of these discoveries pushed back the date of the earliest known version of the DDJ by hundreds of years; the Mawangdui tomb was sealed in 168 BCE, and the Guodian strips date back to 300 BCE.

Now, an even larger find with a Daodejing older than as old as Guodian’s has been uncovered, though it has a shady provenance. These bamboo slips (probably from what is now Hunan, in the old pre-China Chu kingdom) were stolen by grave robbers and sold at auction in Hong Kong. A wealthy alumnus of Tsinghua University bought and donated them to his alma mater in 2008, in muddy waterlogged form, and a careful restoration project is just beginning to bear fruit.

Details are still scarce, but there is a version of the I Ching with sections not before seen, as well as the oldest known Daodejing. It’s as if scholars found an older edition of the Bible, with significant changes from the one we are all familiar with. Wouldn’t you be curious to see how it read?

The background is fascinating, too. In 221 BCE, about a century after these texts were buried, the first Qin emperor (Qin Shi Huangdi) unified China, gave it its name (“Q” is pronounced “CH” in the current Pinyin transcription of Chinese), and began construction of the Great Wall. As part of his efforts to solidify power, he led a vicious purge of dissenting ideas, known in Chinese as 焚書坑儒 (“the burning of books and burying alive of scholars”).

Before this time, for example, there had been a tradition that leaders voluntarily abdicate when their rule had run it’s course, and hand the throne to a distinguished and worthy successor, not a hereditary heir. All traces were destroyed, and the practice is known only through these recently rediscovered documents.

Very few texts survived this purge, which Dartmouth scholar Sarah Allan says amounted to “a literary holocaust.” Only texts buried in tombs were safe. But the Qin paid a price. Qin Shi Huangdi’s son and heir apparent, Fusu, warned his father that the purge — especially attacks on Confucianists — would cause instability and an early demise for the empire. Fusu was exiled and later forced to commit suicide because of his dissent, but his prophecy was borne out when the empire collapsed in 206 BCE after only 15 years.

And Fusu got the last laugh, going on to a successful second career as the star of the popular video game Prince of Qin.

Hi Mark,

Nothing prior to the Guodian Laozi has been found yet. The paragraph in the article you cite is misleading. It reads:

“The Tsinghua manuscripts and the two other collections, also dated from around 300 B.C. … together include … the oldest version of Laozi’s “Dao De Jing”

The most recent tomb-text of the Laozi is a Han dynasty text: http://warpweftandway.com/2013/03/31/transcription-of-beida-laozi-manuscript-on-line/