DISCOVERED:

A lost section of the Tao Te Ching

What is below is soil, but we call it ‘earth’.

What is above is vapor, but we call it ‘heaven’.

We use the designation “Tao,” but may I ask its name?

Those who use “Tao” in their work must know and trust its name.

Thus, their work is accomplished and they endure.

When a sage does her work, she necessarily knows and trusts its name,

Thus her meritorious work is achieved and she goes unharmed.

The names and designations of ‘heaven’ and ‘earth’ stand side by side.

Hence, if we go beyond these areas, we cannot think of the appropriate name.

[The heaven is deficient] in the northwest; due to violence, the earth below is too high and firm.

The earth is deficient in the southeast; due to violence, the heaven above is too wide and pliant.

The way of heaven values weakness.

Paring away at the full grown serves to help the newborn,

Attacking the strong and punishing the {text missing}

That is why what is insufficient above has an excess below,

And what is deficient below, has an excess above.

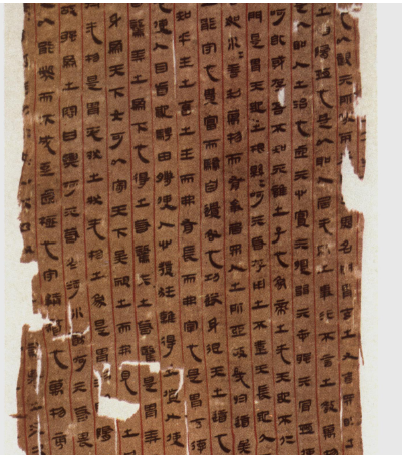

That is (my English rendering of) a lost section of the Tao Te Ching, found on ancient bamboo slips discovered in a tomb in China. It is not included in any printed version of the Tao Te Ching, aka the Laozi or Daodejing. (There is a lot of nuance and terminology here that’s hard to spell out succinctly. I go into some of it at the end of this post.)

With any book as old as the Tao Te Ching — 2,400 years at a minimum — you can be sure that it has been changed over the centuries by mistakes in copying, editorial “improvements,” or political censorship. But this is the first time any lost passages from the original have been found in over 2,000 years, as far as we can tell. Like the Gospel of Thomas, a Christian text dating to as early as 50 C.E that was found buried in the Egyptian desert, this long-hidden text may give us a glimpse of original spiritual insights before they were altered by later editors, or simply lost.

Most modern editions and translations in the last thousand years have been based on Wang Bi’s version, which he first wrote down shortly before his death in 249 C.E., at age 23. But at least four older texts have been discovered:

1. The Guodian bamboo strips (300 B.C.E. or earlier)

2. The Mawangdui silk texts (168 B.C.E. or earlier)

3. The Beida bamboo strips (150 B.C.E.), donated to Peking University in 2009. (Beida is the Chinese nickname for the school, whose full name is “Beijing Daxue”)

4. The Fu Yi “ancient version” or “concubine version” (It was written down in 574 C.E. and said at that time to have been based in part on a text found in a tomb — sealed before 202 B.C.E. — which belonged to the King of Chu’s favorite concubine.)

By all accounts, the Guodian version is the oldest. It was found, in 3 bundles, in the tomb of a person connected to the King of Chu, who may very well have been the tutor to the Prince Qingxiang 頃襄. It does not include all of the classic, and the second half of chapter 64 is repeated in the first and third bundle, with some differences. This suggests that the bundles may have been copied from different originals. None of the chapters we now number as 67-81 are present.

The third bundle contained 14 bamboo slips with text not found in any other version of the Tao Te Ching. In the first book that published the new texts, the Chinese work “Guodian Chu mu zhujian,” the authors considered it to be a separate work that got mixed in, and gave it the name “Taiyi shengshui” (“The Great One produced water“).

8 of those slips contain a distinct and separate cosmogony fitting that title. But Professor Allan makes a compelling case that the other six slips — clearly distinct in tone and writing from the first 8, and similar to the Tao Te Ching — are actually part of the TTC, or at least the proto-TTC found at Guodian. (We don’t know if the Guodian slips are THE original version of the Tao Te Ching, an excerpt from a more complete version, or one of many raw chunks that the book was eventually built out of.) Many other scholars, including William Boltz and Jennifer Ritchie, agree. Others, including Dirk Meyer, Scott Cook and Scott Barnwell, would keep it separate with the rest of the Taiyishengshui. In the Stanford Encylopedia of Philosophy, Alan Chan writes simply that the Taiyi shengshui “may have formed an integral part of the Guodian Laozi ‘C’ text.”

I don’t have room to go into all of the details of this argument, but she lays it out very clearly in her article “The Great One, Water, and the Laozi: New Light from Guodian” which can be found in the journal T’oung Pao, Second Series, Vol. 89, Fasc. 4/5 (2003), pp. 237-285. For most people, the best way to read this article is through the JSTOR database at your public library. The JSTOR URL is http://www.jstor.org/stable/4528939.

Professor Allan published that article 10 years ago, but very few people are aware that a “new” part of the Laozi may have been found. Perhaps this is because of the rigorous scholarly article in which it is contained, or due to unquestioning acceptance of those first scholars calling it part of a different text, or simply because the title of Professor Allan’s article doesn’t say “Tao Te Ching” in it. And to be fair, there are other scholars who don’t think this text IS part of the original Laozi.

But given the broad interest in this mysterious and important work, it deserves to be better known.

Some nuances and fine points:

Scott Barnwell of the Baopu website gave me a number of excellent finer points on this discussion. Major thanks to him for that help. He has written excellent and much more detailed discussions of early Daoism in a series called “Classical Daoism — Is there really such a thing?” which I highly recommend. I’ve incorporated some of Scott’s corrections above; here are some more.

The name Tao Te Ching (or Daodejing) wasn’t applied to this work for centuries after it was pulled together, whenever that was. At first it was called “the Laozi” after its reputed author, the same way that the Zhuangzi and other classical philosophy texts were named. So you can’t properly call this “a lost section of the Tao Te Ching.” It would be more accurate to say that it may be a lost section of the Laozi — or perhaps a chunk that was edited out as the final work was coming together.

Chapter 64 of the Laozi is present as two separate chunks in the Guodian bamboo strips, and they were most likely seen as separate chapters at the time. The second half is the part that was repeated. The chapters at Guodian were in a completely different order, and not separated into the two big sections (“Dao” and “De”) found in the received version. There’s good reason to think that what we now call chapters 67-81 did not exist back in the Warring States period; a commentary on Laozi in chapters 20 and 21 of the Hanfeizi text written at least 50 years later doesn’t mention any of those chapters either, implying that Han Fei was reading a version of the Tao Te Ching that didn’t include them either. (Without this implicit confirmation of their absence, it’s possible that those chapters were simply lost, stolen by graverobbers, or uninteresting to the person who assembled the Guodian bundles.)

Wang Bi wrote a commentary on the Daodejing (calling it that), and there is a copy of the book attached, but Rudolf Wagner has demonstrated that the attached Daodejing is not actually the one that Wang Bi was referring to. Another mystery. Wang seems to have been referring to a text much closer to the Fu Yi and Mwangdui versions than to the received text.

The Guodian bamboo strips are just that, separate distinct little strips of bamboo — a bit like computer punch cards, if you ever saw that old technology. And like them, if you drop a bundle on the ground, there’s no easy way to tell what order they were originally in. Scholars look at nuances such as the precise shape of the strips, their calligraphy, punctuation markings for the end of chapters, and notches from the long-gone strings that bound then. Prof. Allan writes:

“Although the fourteen slips mentioned above have been separated out as a distinct text and given the title Taiyi shengshui by the editors of the Guodian Chu mu zhujian, there is no physical basis upon which to distinguish this material from Laozi C: the slips are the same length, the handwriting appears to be the same, and the markings of the eroded strings used to bind the slips are in the same positions. This suggests that the slips were bound together as a single text.”

Finally, the dates of the texts are conservative; they are at least that old, and might be older. The two oldest were found in sealed tombs, and the year listed is the date when scholars believe that those tombs were sealed. (The Guodian tomb could not have sealed after 278 B.C.E, because in that year the Chu Kingdom was overrun by invaders.) The texts could easily be decades older. The Beida version was stolen (from another tomb, probably), bought on the black market and donated. They were dated by comparison and carbon dating.

Mark,

re: “The name Tao Te Ching (or Daodejing) wasn’t applied to this work for centuries after it was pulled together, whenever that was. At first it was called “the Laozi” after its reputed author, the same way that the Zhuangzi and other classical philosophy texts were named. So you can’t properly call this “a lost section of the Tao Te Ching.” It would be more accurate to say that it may be a lost section of the Laozi — or perhaps a chunk that was edited out as the final work was coming together.”

— Actually, my point applies to “the Laozi” as well. The Guodian bundles do not call it the Laozi. Neither do the Mawangdui texts. You could call these omitted passages of a collection that would later become the Laozi/Daodejing. I personally prefer “proto-Laozi.”

re: Sarah Allan: ““Although the fourteen slips mentioned above have been separated out as a distinct text and given the title Taiyi shengshui by the editors of the Guodian Chu mu zhujian, there is no physical basis upon which to distinguish this material from Laozi C: the slips are the same length, the handwriting appears to be the same, and the markings of the eroded strings used to bind the slips are in the same positions. This suggests that the slips were bound together as a single text.”

— There is also no physical basis to connect Laozi A, B and C either. And it is now well-known that “unrelated” texts could share the same material carrier (i.e. bundles of bamboo slips or pieces of silk).

Thanks, Scott. In an email, he made a very interesting point that I’d like to share here. Above, I write that if we hadn’t seen the Daodejing before, scholars would IMHO definitely group this possible “lost fragment” of the Laozi with the rest, because of its textual similarity and presence in the bundle.

(Though I think the cosmogony in the first 8 slips would be seen as clearly distinct. Prof. Allan proposes that they formed a sort of appendix to the work. Remember that the numbering 1-14 is purely coincidental; we have no way of knowing what the original order of the strips, which were found unnumbered and scattered about. These 14 were grouped together simply because they aren’t found in any other versions of Daodejing.)

Scott counters that if we hadn’t seen the Daodejing before, scholars would consider each of the three bundles as a separate text. That makes sense. Are there enough textual similarities that researchers would think to consider them part of one work? Liu Xiogan has demonstrated that much of the coherence and consistent tone that we find in the received Daodejing was introduced by later editors, slowly and subtly shaping the text to that end by, for example, eliminating articles and shaping lines to be four characters long wherever possible.

Scott’s argument is very intriguing. To really test it I feel like I should assemble a version of the Guodian text in the original order and bundles, and try to read them with a fresh eye. Has anyone done that? Did it look clearly like one text in three parts, or would you have considered it three texts?

I think we might find that these three bundles share a similar vision, just as scholars find many of the other Guodian texts to share a Confucian vision. The presence of rhyme also might incline us to group them together. I don’t know.

A clarification on the ordering of the Guodian proto-Laozi bamboo strips:

As said in note 30a of my Laozi essay, “The three Guodian bundles can be divided into subgroups by observing that some “chapters” begin at the end of another on the same bamboo slip and so must follow it. In bundle A they are (a) 19, 66, 46, 30, 64 (pt.2), 37, 63, 2, 32; (b) 25, 5; (c) 16; (d) 64 (pt.1), 56, 57; and (e) 55, 44, 40, 9. In bundle B they are (a) 59, 48, 20, 13; (b) 41; and (c) 52, 45, 54. In bundle C they are (a) 17, 18; (b) 35; (c) 31; and (d) 64 (pt. 2). We do not know the order of the subgroups within each bundle; that is, for example, bundle A might begin with the (e) chapters.” This doesn’t affect the bamboo strips you’re concerned with, however, as they are all on single bamboo strips and could – as far as I know – have been placed almost anywhere in bundle C.

Good points. The Confucian bent of the Guodian trove generally is a really interesting thing to note, and yet another reason to be cautious about drawing big conclusions.

Chapter 19 in the received text instructs the reader to abandon pointedly Confucian ideas such as “ren” (humanity), “yi” (righeousness) and “sheng” (sageliness.) But the Guodian version of this chapter has other words — discrimination, swindle, and hypocrisy — in their place.

Liu Xiogan and others interpret this to mean that the anti-Confucian sentiment was inserted by later editors but not part of the original. It seems at least as likely to me that a Confucian tutor (or his assistants) copied all of the strips found at Guodian from a larger text, and changed this section they didn’t like to be less offensive (from their point of view). And that later editors working from the original restored its meaning.

Of course, we really have no way to choose between the two theories at this point.

re: “It seems at least as likely to me that a Confucian tutor (or his assistants) copied all of the strips found at Guodian from a larger text, and changed this section they didn’t like to be less offensive (from their point of view). And that later editors working from the original restored its meaning.”

— I think this is quite possible, and maybe even probable.